In 2011, I came across a Techcrunch article titled ‘Tablet Zero’. It chronicled the legal conflict between Apple and Samsung at the time when the iPhone and iPad were still in their infancy, and Samsung had introduced their Galaxy brand to find a foothold in the burgeoning market for personal smart devices. Apple argued that Samsung’s competing Galaxy devices were blatant and shameless rip-offs of its own products. Samsung’s defence was that you can’t own the intellectual property for something as elemental as a rounded rectangle.

Today, all smartphones and tablets look pretty much the same. That’s not because there’s no innovation in the industry, it’s simply because a rectangle with an all-encompassing screen on it is simply the base form for the product. You couldn’t possibly deviate from that elemental form if you were to make a product in that category.

Coldewey states it perfectly:

“…you can’t make a Xoom without making an iPad first, just like you can’t make a die without making a cube first. This was Apple’s stroke of evil genius.”

To this day, Coldewey’s article remains one of the most enduring commentaries on product design that I’ve ever read.

Something I’ve been thinking about recently is the platonic form for a pram — the platonic pram. What would be the skeletal form of the pram that you’d have to start with to create every pram, and would it work if you just stopped there?

I alluded to this in one of my earlier posts “The world deserves better prams”. Below are three popular prams that look mostly the same. Is it because there’s no innovation, or is it because the industry has already found the product’s enduring, skeletal form, and the remaining white space for ‘innovation’ is just on the surface?

Answering that question has been the goal of the design and discovery journey for Eloise over the last several months. If in fact there are practical possibilities for new and distinctive forms, then the hypothesis that the pram industry has stopped innovating rings true and there becomes a way for Eloise to contribute something meaningful to this industry.

Finding this ideal first requires identifying the product’s purpose.

Prams are a device that allows parents to explore the world with their children. As such, it is a utility; of which the practical necessity is to move a baby around comfortably.

But they’re also more than just a utility. Exploration, learning, uncertainty, excitement, and connection are all emotive themes prevalent when starting a new family. A product that addresses these themes by considering prams as a mere transport utility is doing the familial experience a huge disservice. Prams need to also be imbued with intangible necessities too: intimacy being the common denominator.

The design objective behind Eloise is building the most intimate pram in the world. In front of this, are the following principles. This story showcases some of the design ideas we’ve explored, some of which we’ve loved, many of which we’ve thrown away:

Effortless

Users shouldn’t have to think too much about how it works and what it does. The product optimises for user-centricity rather than marketing gimmicks.

Connected

The pram should enhance the connection between parents, babies, and the world. Ultimately, this is about a pram that gets out of its own way, and leaves nothing but connection and exploration.

Organic

Raising and caring for a child is not a prescriptive task. As much as books, blogs, and influencers aim to prescribe methods, child rearing is both messy and instinctual. This is the pram that embraces parental instinct, and is flexible enough to accomodate, rather than prescribe it.

Beautiful

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. This should be a product that respects the individuality of the parent. Becoming a parent doesn’t mean shelving your personality, or ignoring aesthetic considerations.

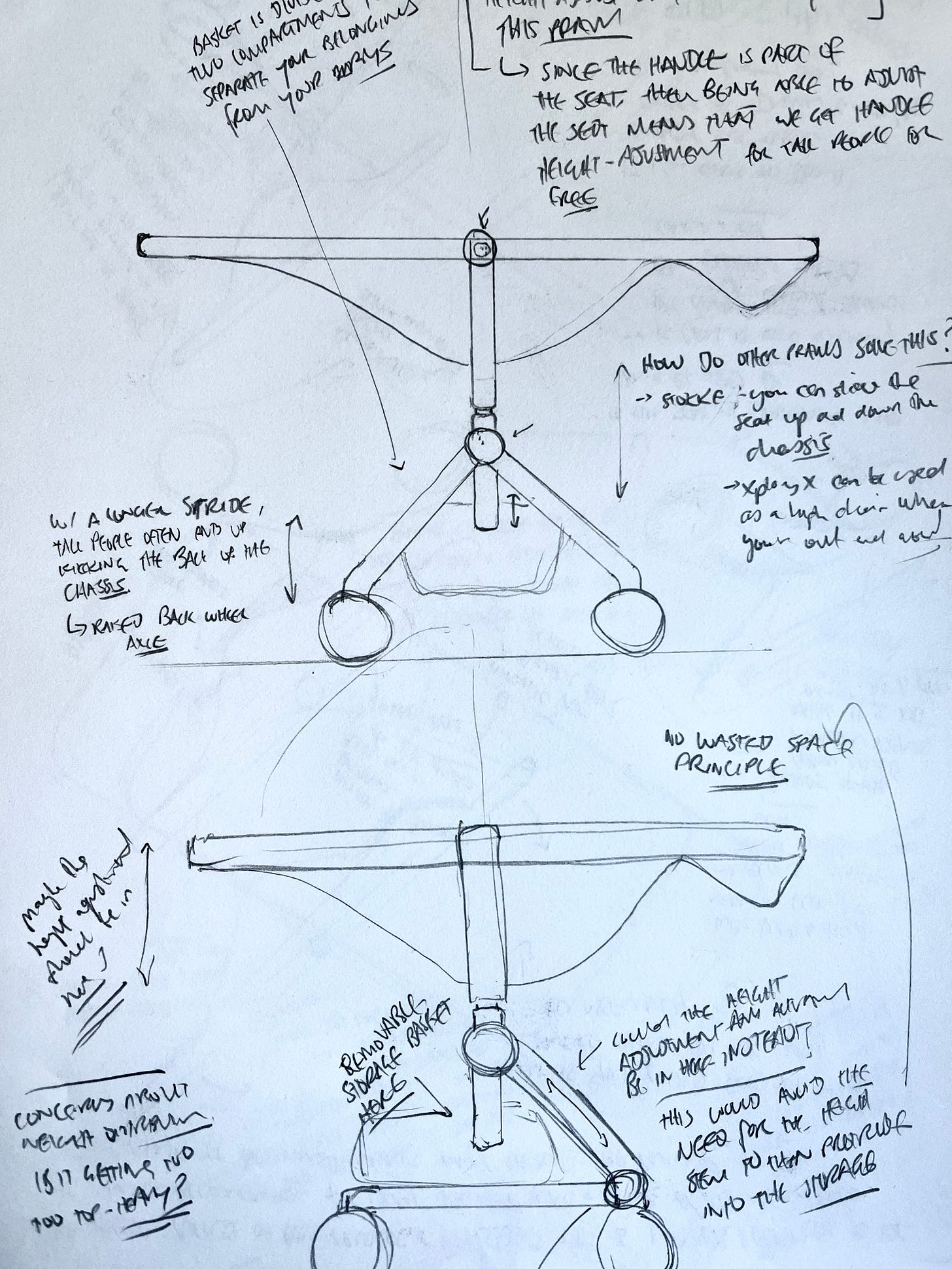

From the scrapbook

Above are some early ideas to enable both a really simple height-adjustment, rotational, and recline mechanism.

Inspired by an office chair which has well-established and universally understood design cues for rotation, height adjustment, and reclining. These features were in service of the ORGANIC qualities of the pram, to provide parents with ease of flexibility to interact with their child in whichever position that felt most natural. By leveraging well understood patterns in chair design, it should be EFFORTLESS for users to adopt. But this design had its challenges, namely it was difficult to find a practical folding mechanism, and the pushbar would impede the rotation of the seat when in its most reclined/bassinet position, detracting from the effortlessness.

The idea of an easily rotatable seat has always been appealing. Most prams have rotatable seats, but they are difficult to rotate because they require them to be detached and then reattached in cumbersome ways. Additionally, prams often can’t fold properly when the seat is in its parent-facing mode. As such, the laborious process means that parents don’t rotate the seat as much as they may want to.

Being able to easily rotate enables CONNECTION, by allowing children to alternate between facing their parent and facing the world in a much more organic fashion. Conventional wisdom suggests that babies should face their parents within the first six months, and then face the world after. In truth, baby’s preferences aren’t genetically hard-wired like this, and there will be many times when a 5 month old would prefer to see the world, and a 1 year old would be required to face their parents. Supporting this kind of ORGANIC behaviour, rather than prescriptive lores, is what this feature is all about.

A design that enables this rotation effortlessly without being impeded by the pushbar could be achieved by a seat design with a raisable pushbar on either end. Therefore when rotating from a world-facing view to a parent-facing view, the user would only need to raise the pushbar from the footrest end of the seat, rather than reach over and pull the single pushbar closer. With these pushbars attached directly to the seat, this design also has the advantage of enabling the pushbars to be used as a handle when the seat is detached, acting like a carrycot.

Some of these ideas culminated in a conceptual design as above. There is an elegance to the seat, dual pushbars, and reclining mechanism being mobilised by a singular, central axis. To the user, it is clear where the rotation points are and there should be no surprises as to the core mechanics of the pram.

Although functional, this design still lacks purity. It feels like a deviation from an ideal form. There are some ideas here to keep, but they need to be further refined and distilled. The pram we aspire to shouldn’t feel like a composition of desired features, it should feel like a cohesive whole.

The journey continues.

Originally published on Medium, July 2023.